Algorithmic Bias

Course Correction

“Algorithms are opinions embedded in code.”- Cathy O’Neil

Introduction Algorithmic bias requires our immediate attention, as it has significant social implications.

Technology will continue to evolve at a rapid pace, but its dynamism must not sway us from our foundational principles of equality and justice.

Terminology Basics1:

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

The use of a computer to model and/or replicate intelligent behaviour, such as learning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

Algorithm

A set of instructions or commands used to carry out a particular operation.

It is the building block for AI to execute the intelligent behaviour mentioned above.

Bias

A particular tendency, trend, inclination, feeling, or opinion, especially one that is preconceived or unreasoned.

Algorithmic Bias

An algorithm is considered biased when systematic and repeatable errors produce unfair or discriminatory outcomes.

Algorithm usage Importance2:

Algorithms have wide use across the public and private sectors. They can process an immense number of variables to make decisions with a speed that surpasses human capabilities.

This is why algorithmic tools have emerged as alternatives to subjective human evaluations in fields such as criminal justice, child welfare, employment, education, and healthcare.

Algorithms are not inherently discriminatory, but they can become biased and amplify disparities.

As seen in Jackson (2018), “Algorithms search for patterns in data. By using past data and inferring meaning from missing data, these models can learn patterns that correlate with social variables (e.g., race or gender) and produce discriminatory results, whether intended or not.”

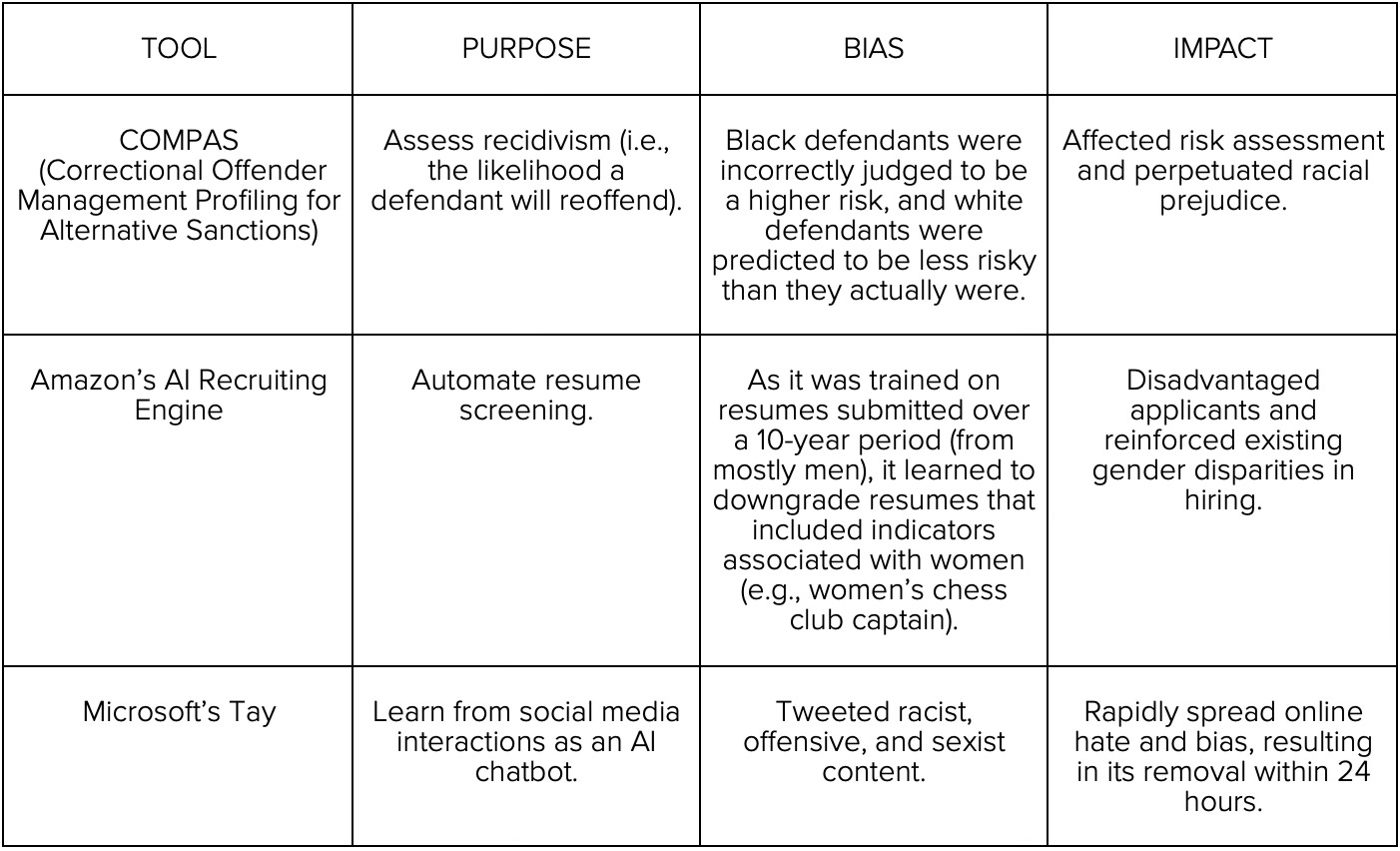

Algorithmic BiasElucidation3:

Two sources have been outlined:

Incomplete or unrepresentative training data

If the data is more representative of some groups of people than others, the algorithm’s predictions may be systematically worse for those unrepresented or under-represented.

e.g., if an algorithm designed to predict mental health needs based on clinic visits primarily uses data from urban areas, it may overlook issues in rural populations, where fewer visits are not due to lower need, but limited access.

Embedded social prejudices

There may be no deliberate effort by developers to include bias, yet patterns reflecting systemic inequities can be inherited and may eventually emerge in the outcome.

“…given that our environment is widely shaped by historical patterns of injustice and discrimination, we can expect many problematic social patterns to be ubiquitous in this way.”- Johnson (2021)

Algorithmic bias causes harms such as:

Allocative-

The withholding of some opportunity/resource from specific groups.

e.g., gender bias in assigning credit limits.

Representational-

Systematic depiction of some group in a negative light, or lack of a positive portrayal.

e.g., age bias in hiring.

“…the impact of algorithmic bias on individuals’ lives can go far beyond one single decision, and prevent, or at least delay, their access to various other opportunities…”- Herzog (2021)

Algorithms require constant monitoring, as bias can enter its lifecycle at various stages.

Major concernsFrom a social perspective4:

Opacity

Even when it’s not a trade secret or hidden behind intellectual property law, most algorithms are ‘black boxes’ whose internal mechanisms are inaccessible.

Not knowing how the algorithm arrived at its decision makes it harder for affected individuals to prove that they have been discriminated against.

Furthermore, there is an assumption that numbers, unlike people, do not lie, so discriminatory results are often overlooked or disregarded.

Feedback loop

This occurs when an algorithm’s decisions affect the real world, and the data generated as a result of this is fed back into the algorithm. Consequently, the same decisions are reinforced, which exacerbates existing bias.

e.g., a crime-predicting algorithm suggests that police patrol a particular neighbourhood. Subsequently, more arrests happen, not because of more crime, but because of increased policing. Nevertheless, the algorithm is validated and keeps targeting the area.

Proxy attributes

Protected attributes, such as race and gender, are sometimes excluded to mitigate bias. However, proxies (whether intentional or inadvertent) can have a false or accidental correlation with the protected attributes they were meant to stand in for.

Jonker and Roger (2024) explain, “…if an algorithm uses postal codes as a proxy for economic status, it might unfairly disadvantage certain groups where postal codes are associated with specific racial demographics.”

It is trickier to detect this form of bias, because the correlation between the proxy (postal codes) and the protected attribute (race) is not always obvious.

Lack of legislation

Most civil rights and anti-discrimination laws were written before the advent of the internet, and the current data protection acts provide insufficient safeguards. Moreover, litigation is rare, so it is unclear how courts worldwide will address algorithmic bias.

However, steps are being taken to address the above concerns.

CounteractionMeasures include5:

Technical

◯ Correction of the vector space

The vector space is where word embeddings are learned. Sometimes, words associated with protected attributes are represented by vectors that perpetuate bias.

Developers try to overcome this by equalising the distance between the protected attributes and the biased concept.

e.g., if the vector model disproportionately associates men with better skills and qualifications, developers can correct this bias by associating the same skills and qualifications with women.

◯ Data augmentation

The algorithm is made to learn from a more extensive range of examples.

For instance, if the original dataset includes the following statement: 'men are qualified and have the right skills’, data augmentation adds: ‘women are qualified and have the right skills’.

◯ IBM’s Fairness 360 is an open-source toolkit that helps detect and mitigate bias in algorithms. Google offers a similar tool called Fairness Indicators.

◯ A human-in-the-loop system, as the name suggests, passes algorithmic outputs to a human who then makes the final decision.

◯ On the research side, the focus is on discrimination-aware data mining (DADM) and ‘fairness, accountability, and transparency in machine learning’ (FATML).

DADM and FATML are integral parts of the algorithmic fairness field, which is at the intersection of machine learning and ethics.

Organisational

◯ Companies have started self-regulating. AI principles are published to address bias, and major technology players such as Microsoft and IBM also have dedicated AI programs and ethics boards.

◯ While not yet universal, AI bias audits are being conducted to prevent discrimination in hiring.

Legal

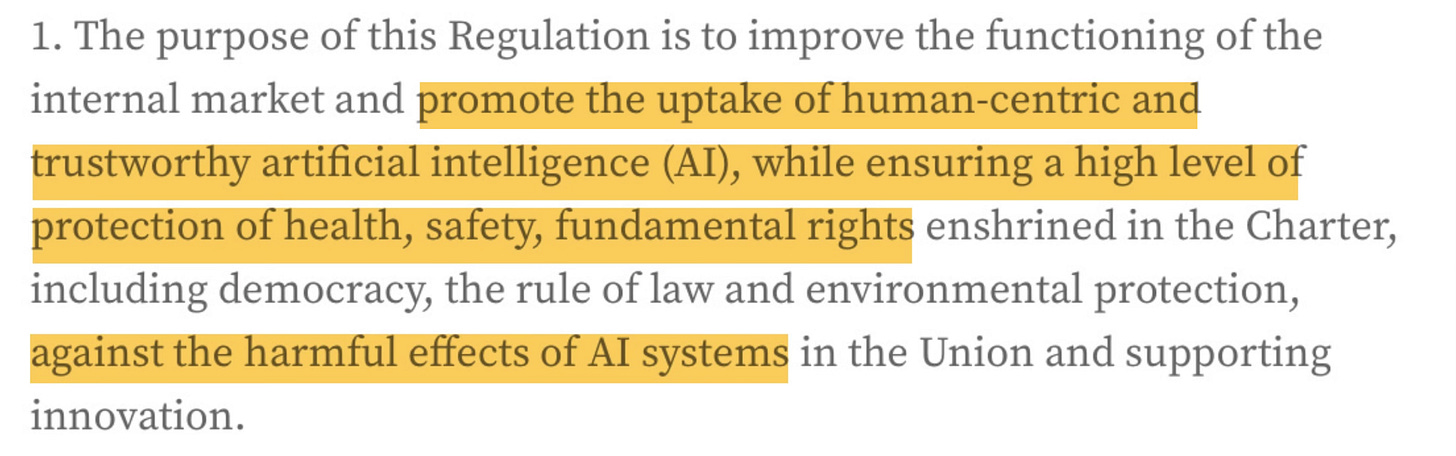

Legislation

◯ In the European Union (EU),

The General Data Protection Regulation grants various rights against algorithmic decision-making, under Chapter 3, ‘Rights of the data subject’, such as the right of access and the right to object. In certain cases, individuals have the right to contest a decision based solely on automated processing.

The Artificial Intelligence Act regulates the use of AI and is the world’s first comprehensive AI law.

Its provisions will become fully applicable in stages.

Soft Law

◯ The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) adopted the OECD AI Principles in 2019.

According to the OECD AI Policy Observatory website,

“ The OECD AI Principles promote use of AI… that respects human rights and democratic values… they set standards for AI that are practical and flexible enough to stand the test of time.”

The principles were updated in 2024 to reflect technological and policy changes.

The OECD Framework for the Classification of AI systems (2022) links the policy implications set out in the above principles to the technical characteristics of AI. This makes it easier to assess the risks and opportunities that different AI systems present, and to strategise accordingly.

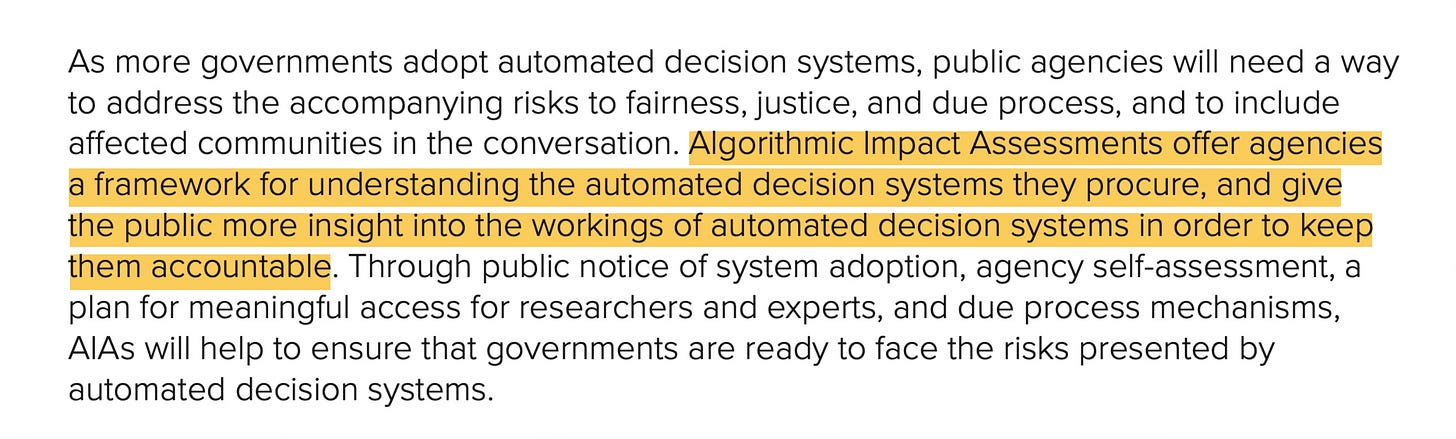

Social

◯ The AI Now Institute released a report called ‘Algorithmic Impact Assessments’ in 2018. As a practical framework for public agency accountability, it proposed algorithmic impact assessments as a tool to evaluate and mitigate bias.

◯ Another non-profit organisation is the Algorithmic Justice League, which ‘combines art and research to illuminate the social implications and harms of artificial intelligence.’ It works toward equitable and accountable AI.

◯ Every year, the Association for Computing Machinery organises a conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency (ACM FAccT). As per the website,

“ACM FAccT is an interdisciplinary conference dedicated to bringing together a diverse community of scholars from computer science, law, social sciences, and humanities…”

It provides a platform to explore critical issues regarding ethics in computing systems.

With these counteractive measures in place, navigating the future becomes less tricky.

Recommendations Addressing algorithmic bias requires a holistic approach. Here are some key points from researchers6:

Diversity

Herzog (2021) states, “Algorithmic design should be a collaborative, interdisciplinary endeavour in which the voices of different groups, with different competences and perspectives, are heard.”

The algorithm can treat individuals with the same true need in an equal manner when it is trained on a diverse dataset that is regularly updated to reflect the real world.

Treatment of minority experiences:

Instead of regarding minority experiences as deviations from a ‘normal’ majority norm, they should be focused on as reference categories of their own. This allows for more accurate data modelling.

Removing protected class variables does little to ensure that the algorithm will be unbiased. As a matter of fact, the machine learning community refers to this as ‘fairness through unawareness.’ Rather, an actionable pathway toward algorithmic fairness must be created.

Transparency

There should be clear disclosure of the data collected and how it is used for decision-making.

A standard of explainability around the working of the algorithm and its limitations is needed.

Organisations must have:

An inventory listing all algorithms currently in use or in development, and a person to supervise its upkeep.

Routine algorithmic bias audits. In the case of any discrepancy, an investigation must follow.

Additionally,

Private and public sector collaboration should be actively encouraged, as it can combine expertise and resources to ensure efficiency and transparency.

Algorithmic accountability laws are required across jurisdictions.

Awareness

All university courses on AI should have an ethics module in which case studies are discussed.

Companies must provide continuous AI ethics training to their employees.

Public campaigns, especially on social media, can help people learn more about algorithmic bias.

If followed rigorously, these recommendations can ensure a more equitable world.

Concluding thought We may not fully eradicate algorithmic bias, but we can create a society where it never goes unchecked.